We tend to think of the teenage years as a time of turbulence; a crazy, tumultuous period in human life that is often marked by stormy arguments, sullen silences, hormones run amok and a roller-coaster ride of befuddling emotions that drive the teenage brain to poor decisions and risky behavior.

The media depicts the typical teenage experience as suffused with insecurities and awkwardness, discomfort with one’s developing body, a struggle for self-identity, a yearning for peer acceptance, and a distrust for persons of authority, parents in particular.

Parents know, only too well, how their teenager can almost seem like an alien species – mysterious one moment, and then wildly emotional and completely unpredictable another. Some ups and downs are inevitable during the teens, but adolescence is also a time when psychological challenges start to take root as stable aspects of the personality – and that can surely impact a teen’s welfare and future.

Sign up for our NEWSLETTER and never miss articles like this one.

Bad behavior can be irritating at best and dangerous at worst, and poor choices can have lifetime consequences or even lead to loss of life. Accidental deaths, aggressive impulses, reckless risk-taking and rule breaking, and binge drinking, spike in the teenage years. It’s also the time of life when psychosis, eating disorders, and addictions are most likely to sink in their hooks. Studies also show that everyday unhappiness and disillusionment reaches its peak in late adolescence.

Historical Tantrums

People often ask, “Is adolescence and all the erratic behavior that manifests around it a recent phenomenon in modern culture? The answer is, most probably not. There are plenty of narratives of adolescence in historical literature that matches our observations of teenage behavior today. Throughout our historical literature, many have cited dark forces that distinctly impinge on the teen.

As far back as 2,300 years ago, Aristotle had come to the conclusion that “the young are heated by Nature as drunken men by wine.”

A shepherd in William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, published in 1623, wishes “there were no age between ten and three-and-twenty, or that youth would sleep out the rest; for there is nothing in the between but getting wenches with child, wronging the ancientry, stealing, fighting.”

A shepherd in William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, published in 1623, wishes “there were no age between ten and three-and-twenty, or that youth would sleep out the rest; for there is nothing in the between but getting wenches with child, wronging the ancientry, stealing, fighting.”

His passionate lament is echoed in most modern scientific inquiries as well. Psychologist, G. Stanley Hall, who formalized adolescent studies with his 1904 Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education, believed this period of “storm and stress” replicated the raw and less civilized earlier stages of human development. Psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud saw adolescence as an expression of agonizing psychosexual conflict.

It is convenient to blame peer pressure or raging hormones for some of this troublesome behavior, but recent studies in neuroscience suggest that there is also a physiological connection that needs to be understood.

Scientists used to think that human brain development was pretty much completed by age 12, but new research has turned up some surprises about the timing of brain maturation and the remarkable capacity for brain plasticity during the adolescent growth phase. In the past decade or so, mainly due to advances in brain imaging technology such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI), neuroscientists have started to look into the interior of the living human brain of all ages to track changes in brain structure and brain function.

Scientists used to think that human brain development was pretty much completed by age 12, but new research has turned up some surprises about the timing of brain maturation and the remarkable capacity for brain plasticity during the adolescent growth phase. In the past decade or so, mainly due to advances in brain imaging technology such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI), neuroscientists have started to look into the interior of the living human brain of all ages to track changes in brain structure and brain function.

So many labs around the world are involved in this kind of research, and we now have a really rich and detailed picture of how the living human brain develops throughout adolescence. In key ways, the adolescent brain is still a work in progress and only completes its development to form the adult brain in the mid-20s.

Inside the Teenager’s Brain

In a longitudinal study of 1800 teenagers over 13 years at the American National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Dr Jay Giedd, has shown that the brain seems to go through a process of developmental restructuring that accounts for both the aberrations of adolescent behavior and the gradual transition to adult maturity.

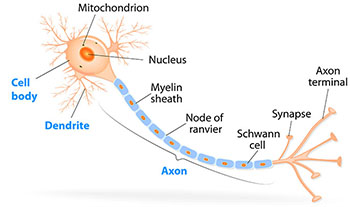

Adolescents apparently lose up to 15% of their grey matter, matched by a corresponding increase in white matter throughout this transition. This process of neural ‘waxing and waning’ alters the number of connections, or synapses, between neurons. Along with the remodeling of the brain is a wiring upgrade as axons (long nerve fibers that neurons use to send signals to others) become more insulated with myelin (fatty white matter). This eventually boosts the axon’s transmission speed by a 100 times.

This process of myelination is critical for learning. If myelination was completed in our teens, we would lose flexibility for all the nimble learning that needs to take place as we separate and individuate from our family.

This period of brain plasticity is also the best time for teenagers to cultivate skills in area like languages,

instruments, sports and the performing arts.

So if a teenager is engaged in music or sports or academics, those are the cells and connections that will be hard-wired for preservation into adulthood. If they are vegetative on the couch playing games, those are also the cells and connections that are going to survive.

Evolution of the Brain

Throughout the adolescent years this slow wave of brain reconfiguration is advancing – starting with the back of the brain and slowly working its way towards the front. Those cells and connections that are used, survive and thrive, while those that are not, wither and die.

Throughout the adolescent years this slow wave of brain reconfiguration is advancing – starting with the back of the brain and slowly working its way towards the front. Those cells and connections that are used, survive and thrive, while those that are not, wither and die.

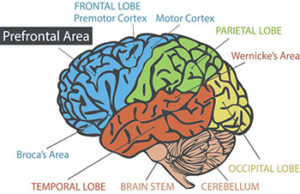

The final part of the brain to be pruned and shaped to its adult configuration is the pre-frontal cortex and this is home of the so-called executive functions such as planning, setting priorities, organizing thoughts, suppressing impulses, weighing the consequences of one’s actions, or governing a tribe.

Much has been made of this discovery of delayed development of the pre-frontal cortex. The fact that the pre-frontal cortex is still growing and re-sculpting throughout the teenage years and into the mid-20s, essentially means that the adolescent brain is functioning without its executive “override”, that tiny voice of caution that keeps young people from reacting impulsively and becoming a statistic for the Darwinian award.

Natural selection swings a sharp edge, and the teenager’s sloppier moments can bring unbearable and tragic consequences.

While the more rational pre-frontal cortex is taking its time to develop, adolescents might be relying on the limbic system, the emotional seat of the brain, to make decisions and solve problems, and this spells trouble.

Part of the limbic system, the amygdala is thought to connect sensory information to emotional responses. Its development, along with hormonal changes, may give rise to newly intense experiences of rage, fear, impulsivity, aggression (including toward oneself), excitement and sexual attraction.

As additional areas of the brain start to help process emotion, older teens gain some equilibrium and have an easier time interpreting others. But until then, they often misread teachers and parents (Feinstein, 2009). You can be as careful and sensitive as possible with your teen and yet have tears, anger and angst at times because they will have misunderstood what you have said.

Chemistry Lessons

Other chemical changes are also taking place in the brain during this period of flux.

For instance, there’s a peak in the brain’s sensitivity to dopamine – the neurotransmitter most responsible for feelings of pleasure.

T he early adolescent brain, with its increased number of nerve cells, has higher levels of dopamine circulating in the prefrontal cortex, but dopamine levels in the reward center of the brain (nucleus accumbens) alter throughout adolescence. These changes in the dopamine levels in the reward center suggest that the adolescent requires more excitement and stimulation to achieve the same level of pleasure as an adult.

he early adolescent brain, with its increased number of nerve cells, has higher levels of dopamine circulating in the prefrontal cortex, but dopamine levels in the reward center of the brain (nucleus accumbens) alter throughout adolescence. These changes in the dopamine levels in the reward center suggest that the adolescent requires more excitement and stimulation to achieve the same level of pleasure as an adult.

So the teenager will attempt riskier behaviors to achieve euphoria. Drug use, gambling, video gaming, pornography, and sexual experiences can all become addictive pursuits as the individual strives to accomplish a dopamine-mediated pleasure.

This vulnerability of the developing brain may well explain why these behaviors identified in adults often have their onset during adolescence or early adulthood.

The teenage brain is similarly attuned to oxytocin – the “cuddle hormone” that makes social connections more desirable and rewarding, which is partly why teens perceive social rejection as almost a dire threat to their existence. To them, the feeling of rejection is visceral. And although they understand the risks of unprotected sex and joining gangs for instance, they tend to give more weight to the pleasures of belonging and inclusion than to their costs or consequences.

Building a Healthy Teenage Brain

This new perspective of the adolescent brain – the ‘adaptive-adolescent’ perspective, can be tricky to embrace—the more so for parents dealing with adolescents at their most infuriating and flat-out scary moments.

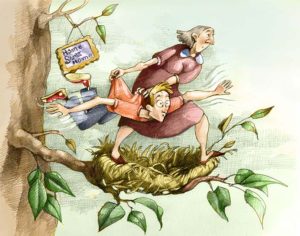

Our teens wield their adaptive brain plasticity amid small but harrowing risks. However, it is comforting to reframe worrisome aspects of teen brain development as signs of an organism that is exquisitely sensitive and highly adaptable – optimally primed to learn how to negotiate its environment and ultimately leave the safe haven of home and move into complex, unfamiliar territory.

This critical process of individuation from the family is the hardest and most important thing adolescents would ever do in their lifespan. It is in the very nature of young mammals to form attachments to elders, care-givers and parents as they provide what Daniel Siegel (2016) refers to as the four S’s – you are Seen, Safe, Soothed and Secure.

Peer Group Madness

But as we mature, we drift away from our parents and look towards our fellow adolescents to form stable peer groups for survival. This process isn’t simply rebelling for the sake of it, but instead is an instinctual motivation, hardwired into our very DNA by millions of years of evolution.

In the wild, when a mammal leaves its parents to become independent and has not established a peer group to turn to for protection, death is inevitable. As a result of this, during our own teenage years, we feel it absolutely imperative to implant ourselves into a social group of some kind, as at the back of our minds, we feel we cannot survive without one.

In the wild, when a mammal leaves its parents to become independent and has not established a peer group to turn to for protection, death is inevitable. As a result of this, during our own teenage years, we feel it absolutely imperative to implant ourselves into a social group of some kind, as at the back of our minds, we feel we cannot survive without one.

In adulthood, this life-or-death instinct towards socializing, dissipates. When a teen approaches their parent stating that they need to attend a particular social gathering, they say this not to exaggerate, but because deep down, they feel they may be rejected if they don’t fit in (Siegel, 2016).

Adolescents therefore are supposed to go through the shenanigans that drive their parents crazy. That’s how they separate from parents, discover who they are, test their limits and learn some hard and enduring lessons in preparation for adulthood

Professor Frances Jensen in her book, The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adult (2015), offers practical suggestions for how parents can help teenagers weather the storms of adolescence, and reap the most from their incredible developing brains. Prohibiting the pitfalls of adolescence alone is not sufficient; teenagers need to be attracted to positive alternatives. Parents would bode well to allow their teenager to take some healthy risks. New and different experiences help your teen develop an independent identity, explore grown-up behaviors, and move towards independence.

Parenting Your Teenager through the Stormy Years

Here are some tips for encouraging good behavior and strengthening positive brain connections:

1. Educate your adolescent about his developing brain.

Understanding the neuroscience behind this important period of growth might help teenagers process their feelings, regulate their emotions and manage their behavior for risk.

If teenagers receive timely insights on their enormous capacity to influence the changes due to brain plasticity, they can hardwire their creative endeavors. Entrusting them to take personal responsibility for shaping their brains becomes an exercise in empowerment.

2. Provide boundaries and opportunities for negotiating those boundaries.

Young people need clear structures, guidance and limit-setting (although they will never admit to it).

Setting good boundaries is one of the best ways to reduce conflict, improve and preserve good communication channels, and build trust in your relationship with your teenager.

Boundaries are the means by which parents calibrate the rate of change and help teens find a reasonable and balanced approach to growing up.

Allow teens to take on more responsibility a little bit at a time. Negotiate boundaries when setting them. Let your teen make their case and allow them to hear your reasoning.

When your teen makes a reasonable point, acknowledge it by making the relevant concessions. The lack of negotiation increases the frequency and intensity of adolescent-parent power struggles and the likelihood of extreme, “all or nothing” outcomes (e.g., running away and physical altercations, outright defiance). Ultimately, it diminishes the opportunities for gradually and safely shifting power and responsibility from parent to teen.

Make a short list of non-negotiable rules that respect family rituals and ensure safety. The most effective strategy to direct teens is by using the “just the facts” approach in a tone of respectful authority.

You are not asking, pleading, or trying to please in order to get them to respect non-negotiable boundaries. You are simply stating the expectation in a calm and direct manner.

The non-negotiable rules are fewer and take the form of things that could be dangerous or illegal (e.g., drinking and driving; the dangers of unprotected sex, excessive computer usage and experimentation with drugs)

3. Talk through decisions each step of the way with your teen.

Ask about possible courses of action your child might choose, and talk them through potential consequences. This flows smoothly when parents have already set the foundations for respectful, open, non-judgmental channels of communication. Encourage your teen to weigh up the positive consequences or rewards against the negative ones.

In the face of resistance, understand the need they are trying to meet through their behavior. The behavior might be dysfunctional but the need rarely is.

Some common needs and the way your youngster might meet them are:

- the need to take flight and escape from the world for a while (they might try to meet this need by spending excessive time online playing games or engaging in social media, or hiding in their room and avoiding homework and chores).

- the need for approval (this can lead to being seduced by peer groups who offer a sense of belonging, and makes them feel important, or helps establish an identity or independence from the family).

- the need to feel independent from you, their parent (this usually manifests as disconnecting and distancing behavior that is often volatile eg. arguing, hostility, defiance).

Reject the behavior but validate their need – because under even the most perplexing and frustrating behavior lies a need that your adolescent is yearning to meet. You could convey: “I get that the world expects a lot of you right now and it’s probably really tempting to want to run away and escape it. I really get that. But spending hours in your room playing online games isn’t the way to do it. Let’s talk about ways you can get what you need, that will work better for you”.

4. Help your child find new creative and expressive outlets for his feelings.

Remember your teenager is using the amygdala, the emotional centre of the brain to process information. He might be grappling with angsty emotional surges that need channeling into creative expression.

Spontaneous and emotional creativity have been known to emerge from the increased activity in the amygdala in your brain during this phase of growth. This is the rare kind of creative moment that can be quite powerful – something great artists and musicians describe.

Guide your teen to tap fearlessly into his emotions and use passion and creativity when working through a big challenge.

Stimulating the amygdala with regular practice can help you enter a psychological state of flow. Being in the flow is often described as having a single-minded focus and joy that comes from losing oneself in productive activity.

As adolescents begin to move away from families of origin as their primary source of support and security, into the social milieu of peers defined by similar motivations and immature skill sets, the role of the helping care-giver and parent is a bridge over troubled waters. We are their testing ground for entrée into the world of independence and autonomy.

Authentically extending ourselves to youth is the greatest gift we can give.

Could you or someone close benefit from counseling or psychotherapy? Take the first step, EMAIL us now, or call (214) 918-8570 (USA), +65 9742-6259 (Singapore). You can also read our client & peer TESTIMONIALS, review the PACKAGE PRICING, or simply find out more about Us.

Counseling & Psychotherapy for life, love, and well-being.

References

Chamberlain, A. F. (1904), Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education. By G. Stanley Hall, American Anthropologist, 6: 539–541.

Feinstein, S. (2009). Parenting the teenage brain: Understanding a work in progress. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

Giedd, J. N. (2008). The teen brain: insights from neuroimaging. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4):335 – 343.

Jensen, F.E. & Nutt, A.E. (2015). The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults. HarperCollins Publishers.

Siegel, D. (2016). Daniel Siegel: Why Teens Turn from Parents to Peers. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thxlUme7Pc8 [Accessed 09 Jan. 2016].

0 Comments Leave a comment